Deep Dive: Constellation Software ($CSU)

>40% Upside Potential

Grab a cup of coffee for this one. It’s one of our most in-depth reports.

The year was 1996. FlightSafety International, founded in 1951 by the visionary pilot Al Ueltschi, was a highly reputable provider of flight simulator training for both corporate and military aircraft. FSI wasn't just a training provider. It would manufacture the training simulators and own a proprietary network of training schools and programs. The company was critical to the safety of the aviation world.

The founder, in his seventies by the mid-1990s, was seeking a succession plan. He had received numerous offers from large corporations and private equity giants to acquire his company, but he refused to sell to them. He was worried that they might see his life’s work as a bunch of assets to be leveraged and financially engineered for profit. His highest priority was that FSI’s reputation as the best provider of safety training programs and simulators should not be compromised. Hence, his priority wasn't to get the highest bid for his company, but to partner with the right set of people.

The Simple Deal

Warren Buffett was introduced to FSI through his own pilots who were being trained on the company’s simulators. Buffett, as he often does, did not want to fix the company; instead, he wanted to preserve its culture of excellence and provide it with the ultimate safe harbor. He understood that FSI’s value lay in preserving the stability of the business and that would require a hands-off approach.

Buffett and Ueltschi met in New York over Coke and fast food. There was no army of lawyers and investment bankers. Instead, Buffett offered to buy FSI for $50 per share in cash, while FSI was trading at $44 per share. He paid a premium to FSI’s market valuation and acquired the firm for $ 1.5 billion.

He also gave the founder what he was looking for:

Autonomy: FSI would operate as an independent subsidiary of Berkshire, and the parent company would not have any say in the day-to-day working of the company.

Continuity: The management team would continue to operate the business as they did before the deal.

That was it. The two men shook hands, and the deal was sealed.

There is another investor who operates in the exact same way — Mark Leonard and his company, Constellation Software.

Founders are okay to sell to him at a lower valuation than they would get from VCs or other Private Equity companies, since he, just like Buffett, offers a hands-off approach and has built a reputation for being founder-friendly.

Welcome to Rebound Capital. If you are new here, we conduct deep research into beaten-down stocks and study companies that made a successful comeback. Subscribe for free and join 6,600 other investors to make sure you don’t miss our next briefing:

Business Overview

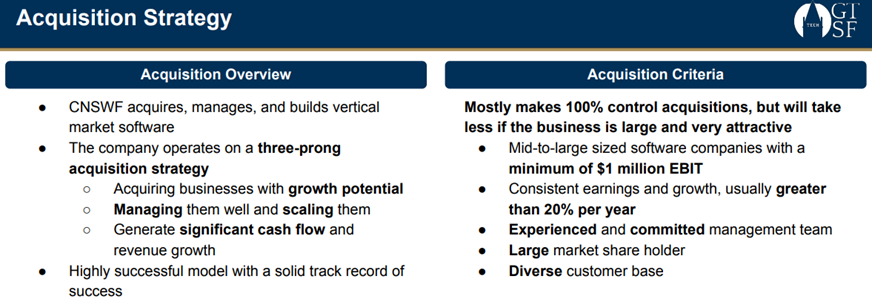

Constellation Software (CSU — Canadian-listed) is one of the most unique investment holding firms we have come across. Typically, institutions that serve as investment vehicles tend to diversify their investments (Berkshire Hathaway is a notable example). In CSU’s case, they have exclusively focused on buying and managing Vertical Market Software (VMS) firms. Constellation Software has acquired over 500 companies since its founding in 1995. They focus on small software firms generating <$20M in revenue. In a way, they are like a private equity firm that never exits its investments.

CSU has six subsidiaries, and it gives them autonomy to operate independently while CSU provides operational advice and financial support. In fact, CSU acquires new companies in a decentralized fashion, where it gives business units the authority to make acquisitions on their own. Only large acquisitions need approval from the head office.

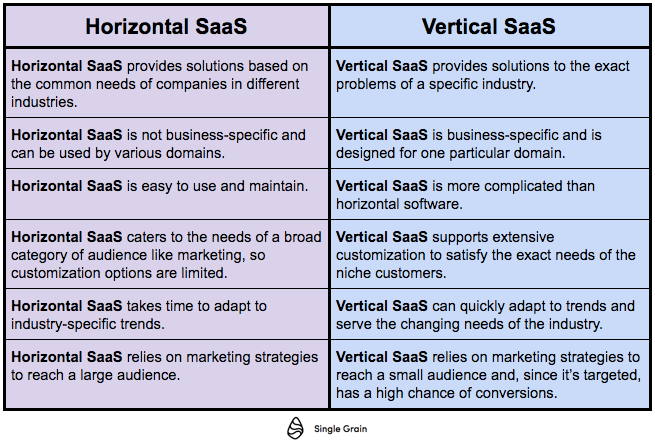

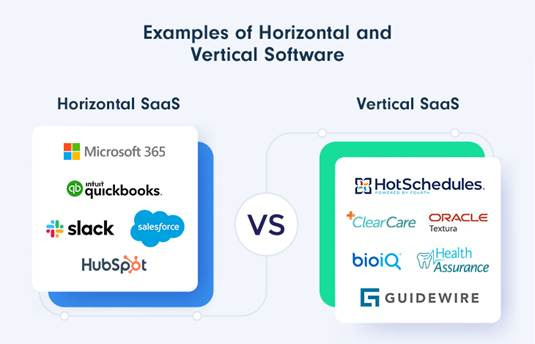

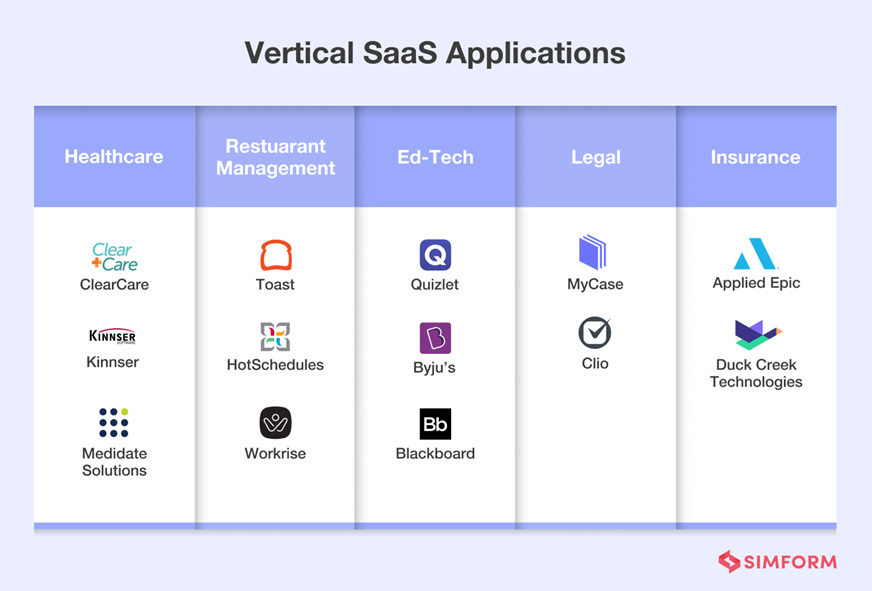

What is Vertical Market Software (VMS)

VMS is software designed specifically for a single industry or market segment. This is in contrast to horizontal software, which is intended for use across multiple industries. An example of VMS is software designed to maintain electronic health records, which helps doctors better diagnose and treat patients.

How Constellation was designed

Mark Leonard founded Constellation in 1995 with $25M in capital. Leonard used to work in venture capital, and he sourced this $25M in capital from former colleagues at Ventures West Capital and Canadian pension fund OMERS.

Since its very founding, Mark’s strategy was unconventional. Instead of the usual venture capital playbook of investing in and then exiting companies, he formed the company to buy and hold vertical software firms forever. He wanted to build a permanent capital vehicle. This is an exceedingly rare phenomenon, with the only comparable example being Berkshire Hathaway!

Working in the venture capital industry, Mark grew increasingly frustrated with their obsession with finding companies that could turn out to be very large successes. He noticed that VC firms always chase the high-risk, high-reward companies while ignoring an extensive collection of stable, profitable businesses: the niche VMS companies.

He was convinced that VMS firms had very strong competitive advantages. They were mission-critical and deeply integrated into their customers’ operations. They could tailor their solutions to meet the needs of their end customers. All these factors led to extremely high switching costs and sticky cash flows.

How Constellation built its winning formula:

CSU’s record speaks for itself:

Revenue growth of >25% CAGR between 2000-2024.

Revenue growth of ~21% CAGR between 2015-2024.

Stock has delivered gains of 22% CAGR between Oct’15 – Sep’25.

Stock gains of ~33% CAGR since May 2006.

In fact, CSU’s performance is probably in the league of the best ever if we compare its stock returns from 2006. These stellar returns are a direct consequence of CSU’s unique investment style, its deep adherence to value investing, and to its decentralized model.

Constellation Software’s success was due to a mix of unique characteristics that made copying its style of investing very difficult:

Niche Focus: CSU bought and operated only VMS firms. They focused on the number 1 or 2 players in each vertical.

Focus on segments which are too small for VC/Investment firms: CSU bought firms with <$20M or even <$10M in annual revenue. CSU invested in companies in small segments. This is due to lower competition in these segments, as large financial institutions could not invest here (it would not move the needle for them).

Focused on small and boring companies: CSU was also willing to invest in VMS in sectors generally considered boring or those that were not on other investors’ radar.

Reputation of founder friendliness: CSU quickly developed a reputation for being founder-friendly. They would preserve the company culture and management post buyout. This was highly attractive to many prospective sellers.

Decentralized Model: As CSU grew in size over the years, Mark delegated the investment decisions to sub-division in the company. He set the guiding principles for investing in companies, and the head office would intervene only if the investment amount was above a certain threshold.

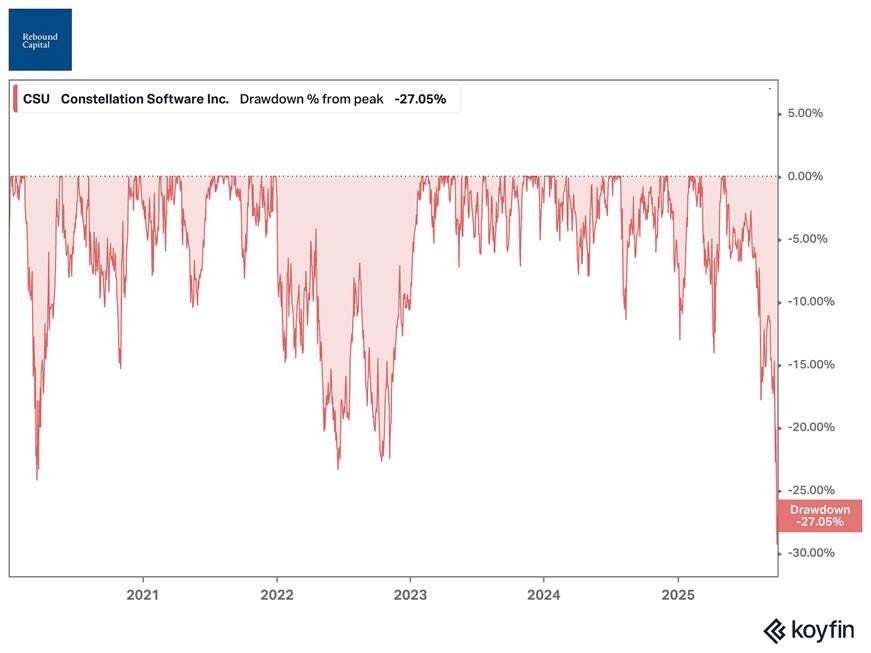

Why is the stock in a drawdown?

Constellation’s stock has dropped by 27% from its 52-week high last week. This is CSU’s largest drawdown in its public history since its IPO in 2006. The company has rebounded strongly, with it being up 10% in the last week (yet overall down 20% from its ATH).

As to what went wrong:

AI Disruption Concerns: The rise of artificial intelligence has investors questioning whether Constellation’s legacy vertical software might become less relevant or easily replaced by AI-powered platforms. Vertical software tends to be highly specialized, but the threat of automation and AI-native tools creating alternatives is real.

Leadership Change: Founder and long-time President Mark Leonard stepped down from day-to-day operations due to health reasons, though he remains on the board. Investors worry about who can carry forward the disciplined capital allocation that made Constellation successful.

Acquisition Environment: Rising prices or scarcity of attractive acquisition targets could slow growth, which is a critical risk given Constellation’s reliance on bolt-on deals.

Let’s dig into each of these concerns:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rebound Capital to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.